SUL BEL DANUBIO BLU- THE BAFFLING BLUE DANUBE By M. Spizzichino

THIS ESSAY IS BOTH IN ITALIAN AND IN ENGLISH- ENGLISH TRANSLATION BELOW THE ITALIAN TEXT

Sul Bel Danubio Blu - Marta Spizzichino

«Fin da Eraclito, il fiume è per eccellenza la figura interrogativa dell'identità» e il suo movimento è una sfida alla fissità dell'identico. Il fiume è anche una sfida allo spazio e — nel caso del Danubio — alle diversità che si dispiegano lungo il suo corso. Se il Reno «è un mistico custode della stirpe», il Danubio «è il fiume di Vienna, di Bratislava, di Budapest, di Belgrado, della Dacia, il nastro che attraversa e cinge, come l'Oceano cingeva il mondo greco, l'Austria absburgica, della quale il mito e l'ideologia hanno fatto il simbolo di una koiné plurima e sovranazionale... Il Danubio è la Mitteleuropa tedesca-magiara-slava-romanza-ebraica, polemicamente contrapposta al Reich germanico».

Il Danubio è l’Europa e la sua letteratura non è che un’estensione necessaria, un corollario imprescindibile. A chi osa affermare che è affluente del Reno, purezza germanica e patria dei Nibelunghi, risponderei piuttosto che è la Pannonia, il regno di Attila, il ricongiungimento di Oriente e Occidente e che in comune con l’integrità tedesca non ha che una manciata di chilometri nella Selva Nera. È lungo il Danubio che le genti si mescolano e non v’è dubbio che in passato deve aver sofferto di questa promiscuità che lo ha reso antagonista del Reno.

Il fiume è per essenza spazio e materia fluida e Danubio di Magris emula queste acque per mole, forma e potenza narrativa. Più di 400 pagine raccontate con una prosa ibrida, lontana dal saggio come dal romanzo, in una struttura sconnessa, vorticante, simile a un torrente in piena. I personaggi, le storie e i luoghi qui evocati si svelano pian piano.

C’è Heidegger che nella Selva Nera costruì la famosa capanna, die Hütte, nella quale da vecchio amava ritirarsi in una solitudine priva di ogni confort. Ed è lì nei paraggi, davanti alla chiesa di San Martino a Messkirch che visse; in una casa bassa, colore beige (…) davanti a cui sorge un albero vecchio e stentato, sul cui tronco qualcuno ha piantato, chissà perché, dei chiodi.

C’è Wittgenstein che collaborò alla costruzione della propria casa nel terzo distretto nella Kundmanngasse, n.19, a Vienna, ora sede della sezione culturale dell’ambasciata bulgara. Un edificio che ha tutta l’aria di essere uno scatolone con le sue forme cubiche incastrate una nell’altra e il suo colore giallo-ocra sporco.

C’è Schönberg, sepolto nel monumentale Zentralfriedhof - cimitero centrale di Vienna - in cui una lapide cubica e storta lo ricorda quale genio della dodecafonia: geometria musicale dissonante e angosciante. E ancora Joseph Roth che visse in Rembrandtstrasse 35, in una casa grigia, in uno squallore di periferia; dove le case sono buie e nel cortile opaco un albero storto sale a sghimbescio - ci stupiremmo se a tale ambiente non fosse corrisposto uno scrittore tormentato e malinconico -.

Chi trascorre un inverno a Vienna rimane forse amareggiato, perché dell’atmosfera color pastello delle novelle di Stefan Zweig non rimangono che briciole; forse solo i caffè che servono al turista di turno la Kaiserschmarrn, ricoperta di confettura di prugne e zucchero a velo.

All’affermazione di Magris: chi ha abitato a Vienna ha imparato a vivere sull’orlo del nulla, come se tutto fosse a posto, replico che forse questo era vero un tempo, quando Karl Kraus, con la sua volgarità da pianerottolo e la ferocia satirica, si riferiva ad essa come stazione meteorologica della fine del mondo.

Muovendoci più a Oriente, verso la Slovacchia, ci si imbatte in fortezze e rocche turrite, traccia di un mondo fiabesco che era e che ora non è più. Castelli costruiti dagli ungheresi per gli ungheresi e guardati dagli slovacchi - che vivevano in drevenice, piccole case cementate da paglia e letame secco - con arrendevole mitezza.

Gli slovacchi sono stati un popolo piccolo che per secoli ha tentato di liberarsi dal disprezzo e dalla noncuranza dei grandi, protraendo questo atteggiamento anche quand’esso non era più necessario. Rivolto a se stesso, assorbito nell’affermazione della propria identità (…), rischia di dedicare tutte le sue energie a questa difesa e di impoverire l’orizzonte della sua esperienza. E ciò non lo rende forse simile a Kafka, che affascinato dalla vita del ghetto ebraico è stato però abbastanza forte da staccarsi dal suo piccolo popolo e percorrere la via della narrazione universale?

Più a est ci accoglie la Pannonia, dove il giallo dei girasoli cede all’ocra-arancione dei palazzi e delle case. È l’Ungheria che nel Settecento il cancelliere asburgico Hörnigk voleva rendere il granaio dell’impero e dove il Danubio ha infilato Budapest come una perla. Numerosi sono i personaggi che la costellano, come il giovane Lukács, che abitava non lontano dal castello di Vajdahunyad e che si riuniva in casa di Béla Balács nel cosiddetto “Circolo della domenica” in cui si indagavano le possibilità di una vita adeguata, pervasa di significato in una stagione storica di instabilità e di crisi (…). Budapest ha il volto della città avveniristica del futuro, con edifici eclettici e storicizzanti, ha i tratti delle metropoli anticipate dai film di fantascienza come Blade Runner: in cui un futuro poststorico e senza stile è popolato da masse babeliche e composite, nazionalmente ed etnicamente indistinguibili.

Spostandoci più a Oriente ci accoglie Canetti al numero 12 di Ulica Slavinska, a Ruse, Bulgaria, in una casa zeppa di oggetti buttati alla rinfusa tra tappeti e ciarpame vario. Autore complesso come i potenti descritti nei suoi libri, che insidiati dai demoni non hanno rinunciato al desiderio del controllo e del potere. Libri impossibili e spigolosi come Auto da fé che ci insegna come il delirio dell’intelligenza possa distruggere la vita e annientarci se accompagnato dalla mancanza d’amore. E ancora Bucarest, la Parigi dei Balcani, città di folla e di Bazar che non rinuncia tuttavia ai parchi verdi e ai grattaceli in stile sovietico anni Cinquanta. È in un quartiere di periferia che vive Israil Bercovici, poeta timido e discreto che con la mitezza ha sconfitto secoli di pogrom e violenze. Quale sia lo statuto della letteratura jiddish oggi non lo può dire, sa che le sue liriche sono sobrie come le avventure che le popolano, certamente diverse da quelle raccontate in passato.

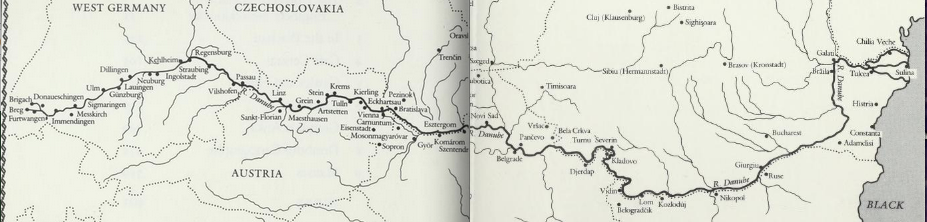

Mancano ancora molti chilometri perché il Danubio sfoci nel Mar Nero e perché ciò avvenga diverse nazioni devono ancora esserne bagnate. Arteria d’Europa e confine dell’impero romano, il Danubio non smette di stupire, per maestà e imponenza. Pensare che sia nato dalla confluenza di due corsi d’acqua - Brigach e Breg - o da una grondaia che spunta da un prato acquitrinoso, mi suscita tenerezza. Mi ricorda che anche lui è stato piccolo e che all’alba dei millenni è ancora in ottima forma.

The Baffling Blue Danube

(*The quotes in cursive reference the Farrar-Strauss-Giroux edition of “Danube” , the English translation of the book by Patrick Creagh )

“Ever since Heraclitus, the river has been the image for the questioning of identity, beginning with that old conundrum as to whether one can or cannot put one foot in the same river’s twice”. The river also defies space and - when it comes to the Danube - the diversity one encounters throughout its path. If the Rhine is a “mythical custodian of the purity of the race”, the Danube is “the river of Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade and of Dacia, the river which - as Ocean encircled the world of the Greeks - embraces the Austria of the Hapsburgs, the myth and ideology of which have been symbolized by a multiple supranational culture…The Danube is German-Magyar-Slavic, Romanic, Jewish Central Europe polemically opposed to the German Reich” *

The Danube is Europe and its literature which glows out of it as a natural extension, a vital corollary. If anyone dares to point out that it’s a tributary of the Rhine, with its German purity and the home to the Nibelung, I would argue that’s actually Pannonia, Attila’s kingdom, where East and West meet, and that it has very little in common with that German ‘integrity”, perhaps just a few kilometers in the Selva Nera. It’s on the Danube that people of all kinds meet, undoubtedly suffering for this promiscuity and becoming the Rhine’s antagonist.

The river is by nature fluid space and matter and the book “Danube” by Magris imitates this body of water in its size, form and narrative power. More than 400 pages that stream into a hybrid prose, neither an essay nor a novel, in a disconnected swirling structure, a raging torrent that bursts through. The characters, the stories, the places evoked, slowly find their ground.

There’s Heidegger who built his famous hut (Die Hütte) in the Black Forest, where he would retire as an old man, seeking a spartan solitude. And he used to live not far from there, in front of the San Martino Church in Messkirch: in a short beige house (…) where you can find an old fragile tree, inexplicably full of nails hammered into its trunk.

There’s Wittgeinstein who helped to build his own house in the third district, in Kundmanngasse, n.19, in Vienna, now home to the Cultural Institute of the Bulgarian Embassy. A building that looks lie a big box “with its series of cubes jammed one into another and its dirty, yellow ochre color”.

There’s Schönberg buried in the gigantic Zentralfriedhof - the central cemetery in Vienna- where a misshaped crooked tombstone reminds us he was a the genius od dodecaphony: a dissonant and eery musical geometry. And then Joseph Roth who lived in Rembrandtstrasse 35, in a grey building “surrounded by the drabness of the suburbs; the stairway is dark and in the featureless courtyard is a stunted tree” - it’s not surprising that it fits with the image we have of the writer, a tormented and melancholic man.

Who spends a winter in Vienna might be disappointed to find out that not much remains of the pastel-colored atmosphere of Stefan Zweig’s novels; perhaps just the cafes who bring to the curious tourist a Kaiserchmarm, covered in plums jams and powdered sugar.

When Magris writes that those who live in Vienna, learn to live on the edge of nothingness, as if everything found its place, I would reply that this would have been through years ago, when Karl Kraus “with the vulgarity of whispers on the landing - nourished his satirical ferocity” talked about that city as “the meteorological station of the end of the world.”

Traveling East through Slovakia, we encounter the fortresses and turreted strongholds, traces of a fairy-tale like world that once existed. Castles built by Hungarians for Hungarians and guarded by the Slovaks - who lived in drevenice, small houses held together by hay and dried manure - with a quiet compliance. The Slovaks: a tiny group of people who has tried for centuries to free themselves of the contempt and indifference of those bigger than them, feeling this way for much longer than necessary. “Turned inward on themselves, absorbed n the assertion of their own identity (…)they run the risk of devoting all their energies to this defense, thereby shrinking the horizons of their experience”

And doesn’t that remind us of Kafka, simultaneously trapped and fascinated inside the Jewish life of the ghetto, but also ready to detach himself from his people in order to become universal?

Heading further East we get to Pannonia, where the yellow of the sunflowers gives way to the ochre-orange of the houses. It’s that part of Hungary that during the 1700s the Austrian chancellor Hörnigk wanted to make the “granary of the empire” and where the Danube pierces through Budapest.

There are several characters orbiting around it, like the young Lukács who lived close to the Vajdahunyad castle and who would get together with Béla Balács in his house in what came to be known as the “Sunday Circle” where they would entertain discussions about the possibilities of a good meaningful life, in an era dominated by crisis and uncertainties (…). Budapest feels like a futuristic city, wit its eclectic architecture that resemble History, it looks like those metropolises foreshadowed by sci-fi moves such as Balde Runner where “a future that is post-historical and without style, peopled by chaotic, composite masses, in national and ethnic qualities indistinguishable”

Eastward and onward, we are welcomed by Canetti at 12, Ulica Slavinska, in Ruse, Bulgaria, in a house filled with miscellaneous objects, thrown together with carpets and bizarre junk. A complex author like the powerful and powerless he describes in his books, haunted by demons so that they couldn’t give up their desire to control and power. These are challenging books like “Auto da fè” who teaches us how an excess of intelligence can destroy life and annihilate us if paired with the lack of love.

And finally Bucarest, the Paris of the Balcans, a city of crowds and bazars mixed with green parks and Soviet-like skyscrapers built in the 50s. it;s at the outskirts of town that lives Israil Bercovici, a shy and reserved poet that stood up to centuries of pogroms and violences, with his calmness. It’s tough to say where Yiddish literature stands today, but we know that his verses are non-pretentious just like the adventures that they capture, definitely different from a heavy past. There is still a long way to go before the Danube merges into the Black Sea and before that happens it flows through other nations. Europe’s artery and the ancient border of the Roman Empire, the Danube never stops amazing us, in its majesty and magnificence. it makes you smile to think that it was the product of two small streams - Brigach and Breg - of a tiny little spring, soaking the wet grass. It reminds me that it was once little too and that at the dawn of the new millennium, is as tumultuous and alive as ever.

Marta Spizzichino, classe ’95, romana da generazioni. Laureata in Filosofia studia ora Biotecnologie ambientali. Escursionista entusiasta, lettrice appassionata, convinta europeista. Cura una rubrica di libri sul giornale della comunità ebraica di Roma SHALOM.it. Ama la lingua e la cultura austro-tedesca, il Bretzel al burro, Primo Levi e Stefan Zweig.

Marta Spizzichino was born and raised in Rome in 1995. She has a degree in Philosophy and she’s now studying environmental biotechnologies. Spirited hiker, passionate reader, big fan of a United Europe. She reviews books, as a columnist, on SHALOM.it, the newspaper of the Jewish Community of Rome. She loves Austro-German culture, a buttered Bretzel and Stefan Zweig.